Challenges of eDiscovery for FCPA Investigations in Japan

Know Before You Go: Collections Complexities in Asia

June 25, 2018

Know Before You Go: Tackling CJK Language Challenges in Cross-Border Matters

July 16, 2018

When discussion of bribery and corrupt business practices comes up, it’s common to think of China and Russia, and the high profile investigations in telecommunications, defense, pharmaceuticals and manufacturing industries.

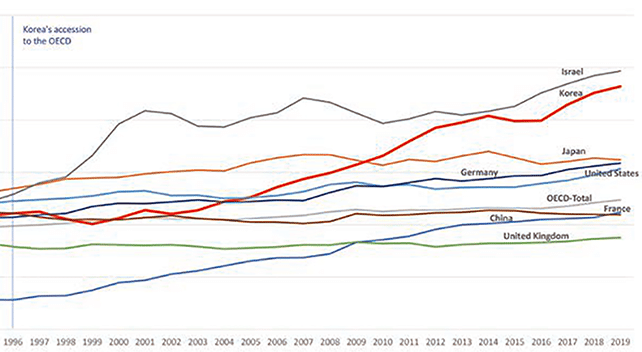

Japan, by comparison, has seen relatively few DOJ and SEC investigations of Japanese companies under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in recent years, but the number continues to grow, as US federal agencies increase enforcement efforts. A historically hands off approach by the Japanese government toward enforcement of anti-bribery laws is giving way to greater awareness and compliance. U.S. anti-corruption laws can be used to prosecute misconduct occurring in Japan, the United States, and even other countries—highlighting the need for multinational companies to ensure that they have robust compliance policies and programs in place around the globe.

An article by Hogan Lovells in Lexology reported that in July 2016, the Japanese Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) published new guidelines on foreign bribery prevention, called “JFBA Guidelines”. The guidelines offer recommendations for corporations to ensure compliance with Japan’s Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), as well as the United States’ Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The process of eDiscovery in FCPA cases, which often involves both criminal and civil phases, is complicated by curious and interesting puzzle of cultural, legal, and technological differences between Japan and the U.S. As an American lawyer who migrated to Japan to gain experience in cross-border litigation, I have had the unique opportunity of being exposed to both sides of a U.S. investigation into Japanese business behaviors. In this post I’d like to share some perspective from the FCPA cases I have managed in Japan as an eDiscovery review manager, and a few tips on eDiscovery workflow and management to achieve the best results while controlling costs.

First it’s important to understand the differences in the legal systems of the two countries. Japan is not a highly litigious society, and the legal services industry has, in many ways, avoided the corporatization of the American legal industry, with 78% of attorneys working in firms of 10 attorneys or less. In Japan there are 287 attorneys per one million people in Japan, compared with 3,769 attorneys per million people in the U.S., according to a 2016 Wall Street Journal report. This is, in part, due to the lack of an adversarial discovery process – discovery in Japan is directed by the Judge, and not the parties. However, in cases where Japanese companies conduct business activities that touch upon the United States stream of commerce, thus subjecting them to American jurisdiction, they quickly find that the American discovery system is far different. Japanese in-house counsel is often surprised at the scope and expense, and formality of the American discovery process, as well as the danger that their confidential business documents and strategies might be shared with a competitor, often in the same industry. Care must be taken to counsel the client on concepts like confidentiality, to process of collection, obligations of legal holds, and other discovery concepts that may be more familiar to an American company’s in-house team.

In the U.S. there is an orientation toward gathering and reviewing documents very broadly, with an aim to understand all the context about the individuals, events and information in the case. In the Japanese system, the judge has broad control over all proceedings, and there is a more focused goal to review and produce only the minimum number of documents needed to support the facts. On FCPA investigations in Japan, FRONTEO works closely with the law firm and client to help them understand both the discovery and eDiscovery process so they can make appropriate decisions about reviewing and producing documents.

To further complicate discovery, the concept of attorney-client privilege as we know it in the U.S. does not really exist in Japan. In the U.S., communications with attorneys for the purpose of seeking legal advice are privileged and usually protected from disclosure, and the ‘privilege’ belongs to the client, with the possibility of waiver if disclosed to third parties. Japan has amended its code of civil procedure to provide for the obligation of attorneys to keep their client’s secrets, but there is no codification of the formal concept of “privilege.” Thus, Japanese attorneys without experience in American litigation are not familiar with our tests for “privilege” and “work-product” which are generally quite familiar to American attorneys. When relying on Japanese attorneys for tasks like document review, it is essential to go over these concepts to ensure a quality review.

Last but not least are the challenges of language. DOJ and SEC enforcement actions under FCPA or antitrust cases typically involve multinational corporations doing business across the globe. So document collections in these cases are most often a mix of multiple languages including Japanese, English, and perhaps other languages. This is representative of the normal mode of communications between subsidiaries, suppliers, sales channels and customers across global regions. The choice of workflows for dealing with these documents (e.g. requiring all documents to be reviewed by a bilingual team, conducting concurrent English/Japanese reviews, workflow for translations etc.) can be very complex and costly if not considered before the start of review.

All of these challenges posed by language, culture and legal concepts in Japan can be daunting. FRONTEO itself is a Japanese company with global operations, and as such we are well versed in cross-border eDiscovery.

In light of the complexities outlined above, I offer the following considerations and recommendations for optimizing workflow and tools in the eDiscovery process for FCPA cases particularly, but most of these comments apply generally to cross-border cases of all kinds:

- Leverage knowledge of cultural and business practices in Japan in conducting searches for evidence related to bribery or corrupt practices. Prior experience in managing document review in response to an FCPA investigation is very valuable. Working on a number of FCPA cases over time we have found that there are similarities in the conversations and terms used when employees discuss pay-offs. For example, in Japan the custom of offering “gifts” or honoraria, to important business partners and clients is much more formalized than in the United States. In many situations these actions may be valid and permissible, but in some situations, similar language may mask illicit behaviors contrary to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. The nuances of language are critically important here, especially for developing effective search terms. Legal and eDiscovery teams must also build a knowledge of the accounting and payment systems and internal financial controls, in order to recognize transactions that are out of the ordinary. Similarities from one case to the next are surprisingly common.

- Set a plan early, and develop regular communications between the eDiscovery project manager and the legal teams, both in Japan and the U.S. Hold a kick-off meeting to review the discovery protocol provided by the law firm, outlining key people, products, business entities and reference information will inform the eDiscovery process. Both the review team and the law firm should be open to potential course corrections to the protocol as new information is revealed in early case assessment and document review as well as continued information sharing via weekly or bi-weekly calls, discussion of “hot” documents, and quality control checks by the firm. In a managed document review, the client, firm, and ediscovery vendor are partners, with each helping the other to understand the facts of the case and build on knowledge each party has to conduct a better review.

- Select a provider who can host the data and manage the project in Japan, but who has offices and experienced teams in the U.S. as well. The availability of bilingual or multilingual review attorneys in both regions allows the project manager flexibility in staffing document review, privilege review, and quality control phases.

- Staff the review to best handle mixed language content. In many FCPA cases involving Japanese companies we conduct the review in Japan, close to the client and legal team. Our staff of bilingual attorneys are very effective at understanding the nuances of the Japanese language, and because they also know English and other languages, they can efficiently review email strings and conversations in mixed languages. Having the review team in the same time zone and region saves time in communicating between the two groups; it’s common for reviewers to raise a handful of questions for counsel on a daily basis, and the 17 hour difference between Tokyo and San Francisco can slow down the process.

- Avoid or minimize document translation; it can be expensive, can add risk (translated content may be challenged by the opposing side) and increases the chance of misinterpretation of nuances in the documents.

- Tools designed for English content do not always work well with CJK (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean) language content. Choose a provider who is aware of and has solutions for Asian language challenges, such as processing encoded content, and support for conversation threading, for example. (For more on the basics of Asian language eDiscovery, see FRONTEO blog posts on “CJK”.)

- Take advantage of TAR (technology assisted review) advanced analytics in early case assessment and in batching documents for review assignments. Rather than review by custodian, we often find it’s far more efficient to batch documents by topic. In a competitive or antitrust investigation for example, batching documents by product family or project, and including entire email threads and attachments, provides the reviewer with a cohesive topic. The reviewer quickly becomes knowledgeable on the issues and events, and can quickly recognize duplicate documents or related information, realizing a much faster review rate as measured in documents per hour. While this requires an upfront investment of time, in the long run it can make your review more efficient and, in the end, more accurate and helpful for deposition and trial preparation.

- Manage privilege identification and review proactively. Search and batch on the names and terms that are likely to be contained in privileged documents. Conduct a focused privilege review, performed by an attorney who is well versed in attorney-client privilege. Conduct a follow-on quality review of documents marked not privileged, to catch coding errors. Having a small team of bilingual American-licensed attorneys stateside to help conduct quality control of privilege or more sensitive documents can be invaluable in ensuring quality across the board for a Japanese review, while avoiding the expense of staffing the entire review with America-licensed attorneys.

Our mission at FRONTEO is to work in partnership with U.S. litigation counsel and local corporate in-house legal to efficiently manage eDiscovery for cases of all kinds, including compliance with FCPA investigations. For readers who are interested in delving further into eDiscovery between US and Japanese companies, I recommend the book by Masahiro Morimoto, founder and CEO of FRONTEO, Inc. entitled “eDiscovery – Japan: A Pathway for U.S. Attorneys to Do Business with Asian Corporations,”.

The book describes how a Japanese-centric eDiscovery service provider can add value, especially in promoting good working relationships between US attorneys and their Japanese clients. With increasing globalization, the book is timely and helpful for multinational companies seeking effective methods of managing US litigation cases.